How to cultivate a “difficult” client

In any work environment, the customer is one of the key factors to set a pivotal way of business development. Sales theory has a long history of tiptoeing around customer needs, customer satisfaction, building trustful relationships, winning customer favor, and resolving problems to ensure an amazing customer experience. In the end, every client wants a product or service that solves their problem, is worth their money and is delivered with outstanding customer service.

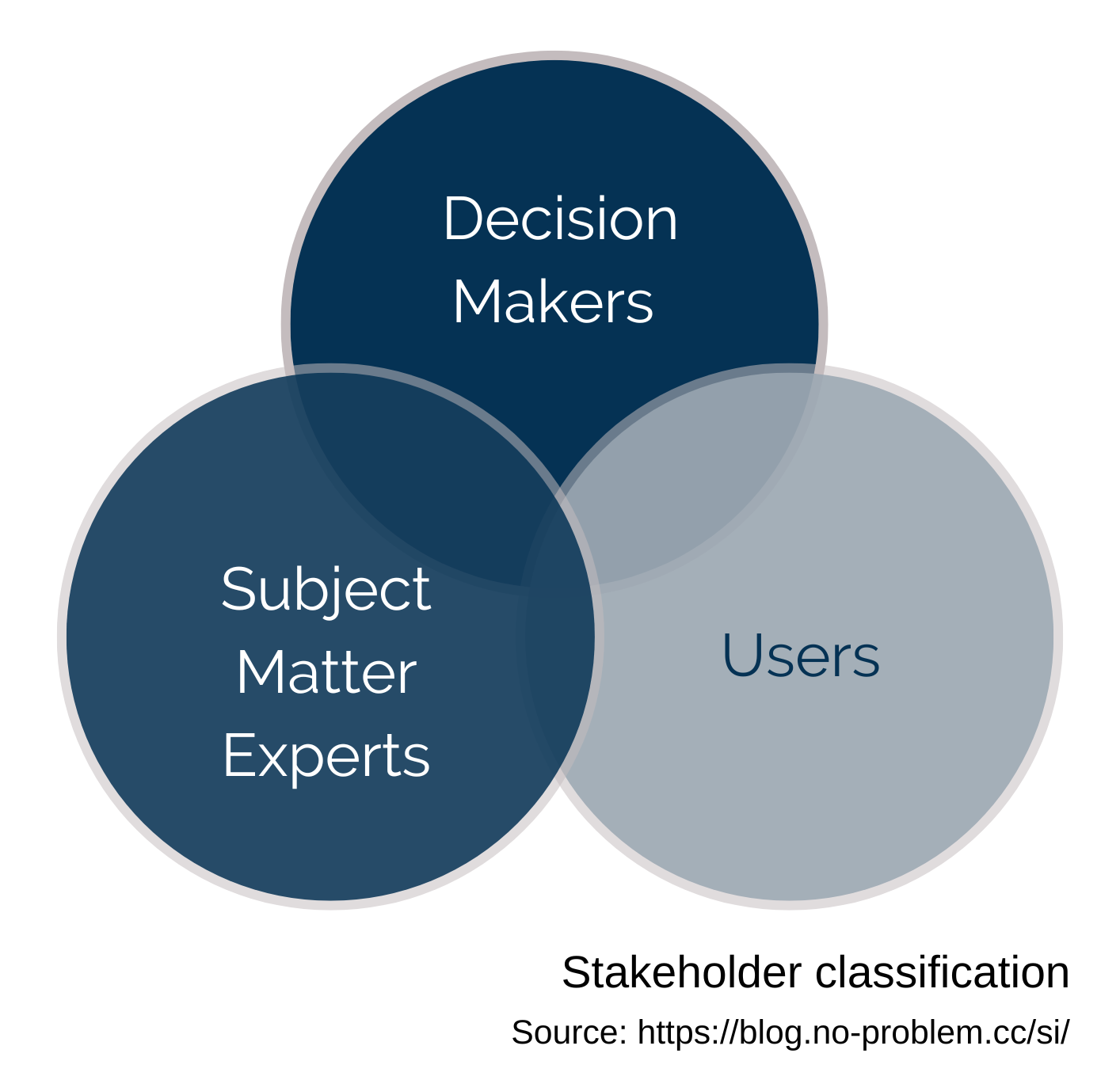

In a service business, besides operational day-to-day activities, unique time-boxed entities aimed to deliver a product/ a service/ a result according to some peculiar customer requirements can be allocated. Each temporary entity is a small project. It has a complexity and settles on the intersection of the interdependent targets: time, budget, and outputs, and possesses a risk of not achieving some or all of these targets. On the customer side usually exist several involved and affected groups with specific clout. These are stakeholders who can support or block a project and its progress. Often they can be clustered into the categories: decision makers, subject matter experts, and users.

For a small project, there is no need to use overly complicated instruments to ensure comprehensive identification, analysis, and fuhrer intentional engagement of stakeholders. However, proper stakeholder management without skipping any stages is vital for any project. It helps reduce a project’s complexity by aligning stakeholder expectations on the project’s goals, scope, and deliverables, recognize concealed political games on the customer side that might affect the scope or slay the project. Stakeholder management is a dynamic process that tracks changes in roles, interests, and commitment of involved groups through all project phases.

The fairness of these statements I’ve learned once again in practice. Recently, a company invited me to take part in their small project with a “very demanding” client. The company is a recognized provider in the talent management market. It has and promotes its own methodology embedded into high-quality products. It was a project with a new client and was supposed to be a door opener for future business. The client is a vast enterprise with a specific corporate culture and established structures, processes, and practices. The project sponsor—one of the new top managers on the client’s side—was familiar with the provider’s products earlier and invited it for the project. The main idea of the project was to replace the existing outdated product on the customer side with a new, deeply customized one.

The provider offers different business services and has to deal a lot with product design, customization, and tailoring activities that require handling of basics of project management. The project manager did a good job. The scheduling was brilliant: logical sequencing, workable deadlines, clear milestones, and planned time reserves. An overview of the existing client’s product had enough details to get a complete picture. The features that must be in a new product were defined. The key stakeholders were known. The project team comprised professionals with a dozen years of relevant experience and possessing the expertise for such projects. A progress tracking system was in place. Each member got a piece of work and the execution began. Everything was fine until the first deadline.

Suddenly, it popped up that the project team and the client had different views on the final product. Even worse, each key stakeholder had her own vision of the product and they provided sometimes opposite comments and suggestions on improvements. Some stakeholders were not aware of or did not realize that the switch to the provider’s methodology would require a change in some working habits. Stakeholders from the users’ group blocked changes in processes. Stakeholders from the experts’ group trusted their own methodology more than the provider’s one. The familiarization of the customer’s experts with the provider’s methodology and users’ training in the new product were not included in the project scope.

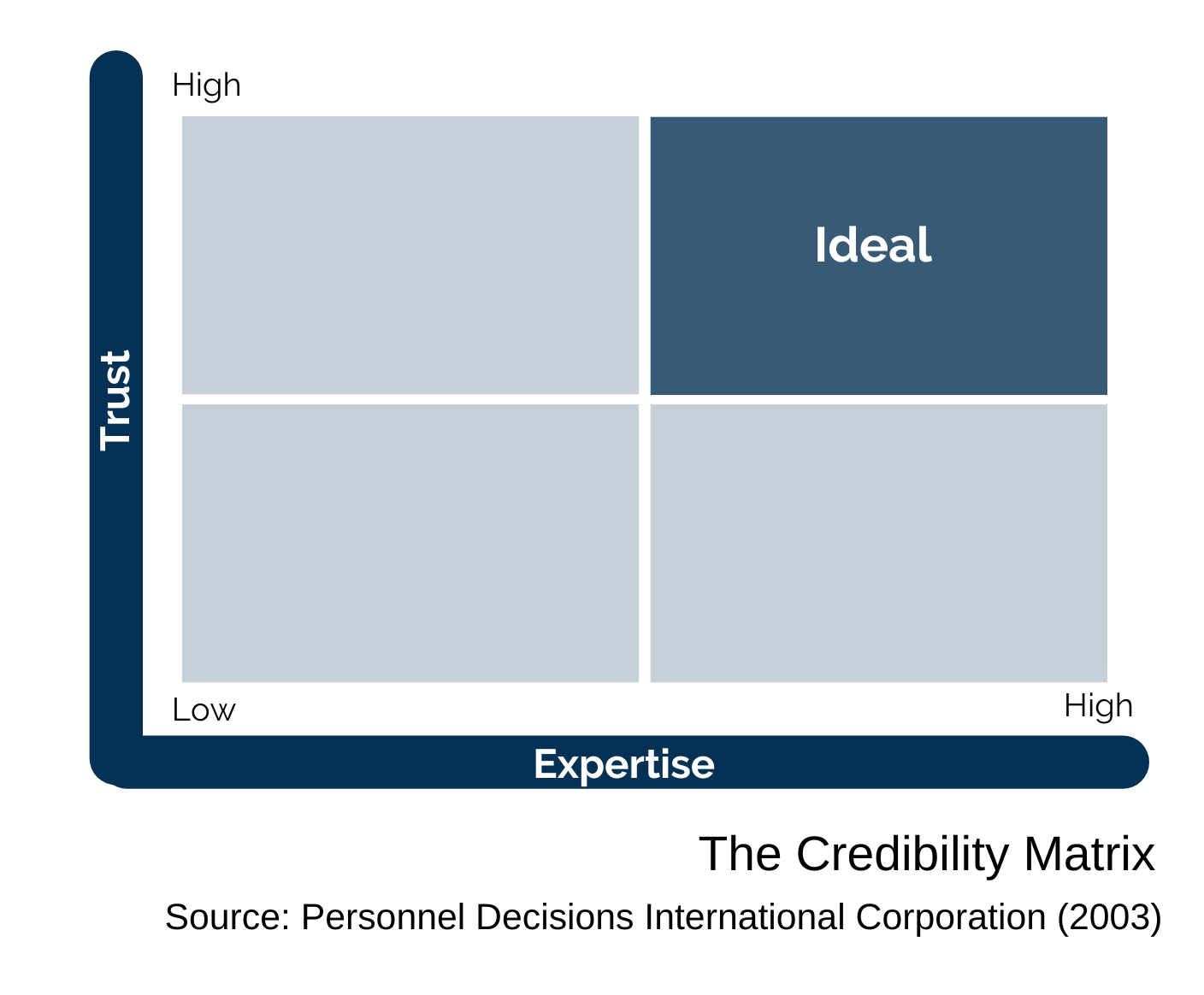

In most cases, the provider operates in or close to the “ideal” quadrant of the credibility matrix. The company has a solid portfolio of easy-going and demanding clients who acknowledge its expertise and trust in its professional advice. Here, the credibility of the new provider for the client’s experts was not high enough to rely on its expertise, so they requested changes to incorporate their old methodology but damaging the project’s essence. The different compromise attempts entailed a waste of effort through several rounds of reworking. A lot of reworking raised a question about the provider’s expertise in product design and produced an avalanche of new contradictory comments and feedback. The product had a good chance of not passing the quality gates. The company‘s focus drifted from the project margin to the reduction of losses.

In most cases, the provider operates in or close to the “ideal” quadrant of the credibility matrix. The company has a solid portfolio of easy-going and demanding clients who acknowledge its expertise and trust in its professional advice. Here, the credibility of the new provider for the client’s experts was not high enough to rely on its expertise, so they requested changes to incorporate their old methodology but damaging the project’s essence. The different compromise attempts entailed a waste of effort through several rounds of reworking. A lot of reworking raised a question about the provider’s expertise in product design and produced an avalanche of new contradictory comments and feedback. The product had a good chance of not passing the quality gates. The company‘s focus drifted from the project margin to the reduction of losses.

Viewed from an observer’s standpoint, it might be noticed that this situation is hardly unique and the hackneyed sales-slogan “one size does not fit all” is undeniably valid for stakeholder management. I am sure that everyone can recall a lot of cases when slipshod stakeholder management created an illusion of stakeholder commitment that subsequently multiplied the complexity of projects and generated problems out of the blue.

Read this article on LinkedIn