Critical Issues and Success Factors in HR projects: Stakeholders

“No matter what you stand for, no matter what your ultimate purpose may be, you must take into account the effects of your actions on others, as well as their potential effects on you.” R. Edward Freeman

You have received a new challenging task — to lead one of the HR projects. It’s awesome! Congratulations! As the first excitement wears off, you are to decide: Where and how to start? What factors, aspects, and specifics should be considered? — and dozens of other questions and points to fulfill the requirements of your project. I’m not going to compete with PMI or Axelos in providing a comprehensive methodology in project management, rather give some practitioner tips on what matters to HR project success and list some valuable sources where to glean further hints and ideas.

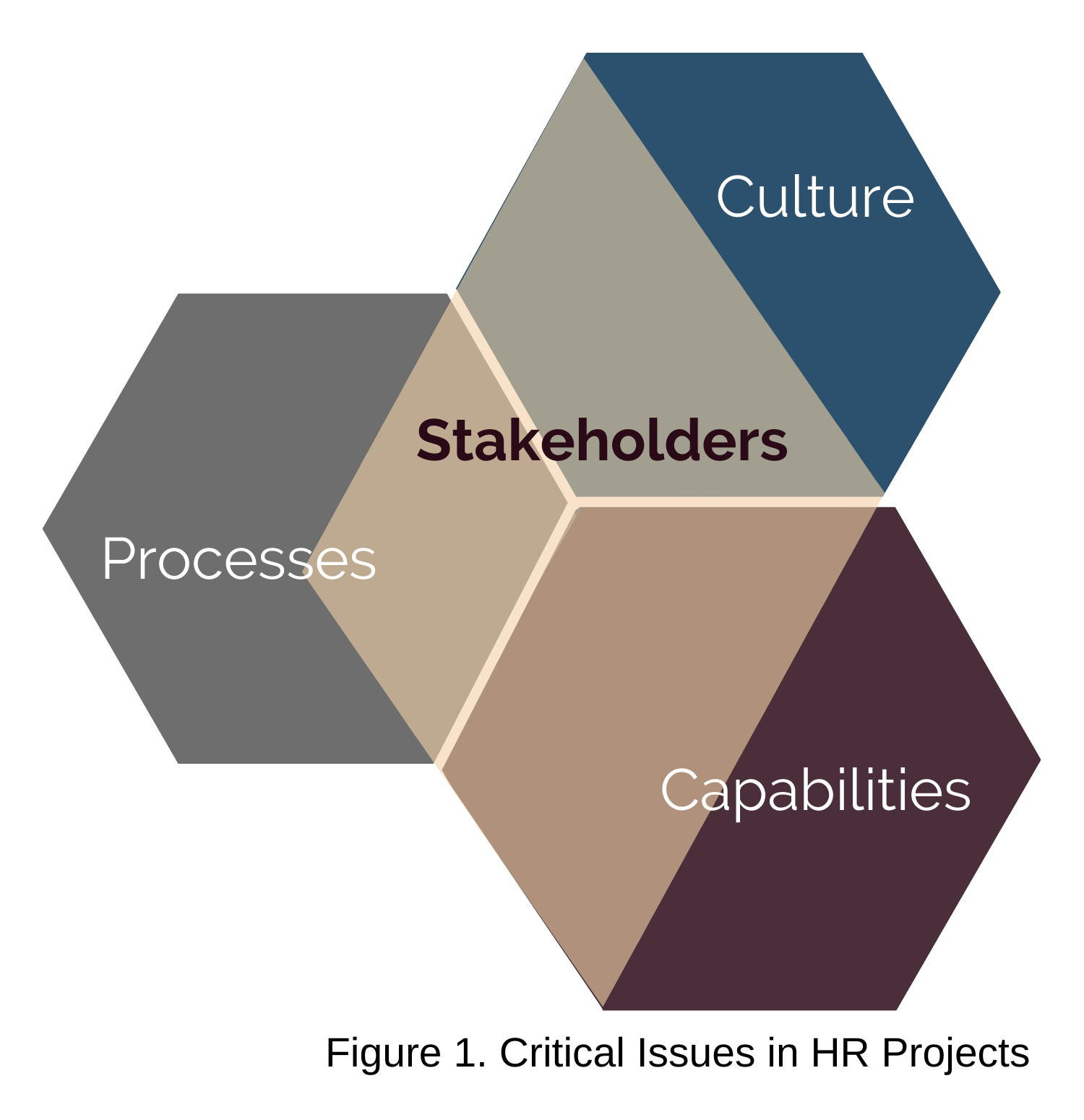

Usually, an HR project is initiated as a response to changes in business strategy, a value-added HR initiative, digitalization of processes, or any combination of these. HR projects are diverse by purpose, nature, duration, available resources, and budget. However, some common critical issues and roadblocks can be present in any HR project (Figure 1).

An encounter with some of them might require significant efforts and additional resources to get a project back on track while facing the full set will most probably prove fatal for project success. On the other hand, proper conscious preventive activities and skillful management empower one to turn these hindrances into powerful project drivers and success factors.

An encounter with some of them might require significant efforts and additional resources to get a project back on track while facing the full set will most probably prove fatal for project success. On the other hand, proper conscious preventive activities and skillful management empower one to turn these hindrances into powerful project drivers and success factors.

One such factor is stakeholders, i.e. groups, persons, authorities, or parties that might have a vested interest in any phase of a project, program, or initiative. Careless or slipshod stakeholder management can bury any project or significantly multiply its complexity. HR projects are not an exception to this general rule. It is well known that even minor changes related to humans might have huge and unforeseen effects. HR projects are dedicated to and dealing with people. Sometimes it is not easy to predict the entire range of potential reactions of the affected groups and individuals and build up a complete overview of them.

Stakeholder identification

The first core step to success in any project is the proper identification of stakeholders. There is a wider range of stakeholders which may affect, or be affected by, an HR project. These stakeholders may be internal or external to a company and may become supporters or blockers of the project and its progress. For most HR projects, there is a need for involvement of other departments, such as IT, finance, communication, etc., that favor classification of stakeholders into the following categories:

- upward (sponsor, steering committee),

- downward (project team and contributing experts),

- outward (providers, employees, regulators) and

- sideward (peers who collaborate in sharing resources and/or information).

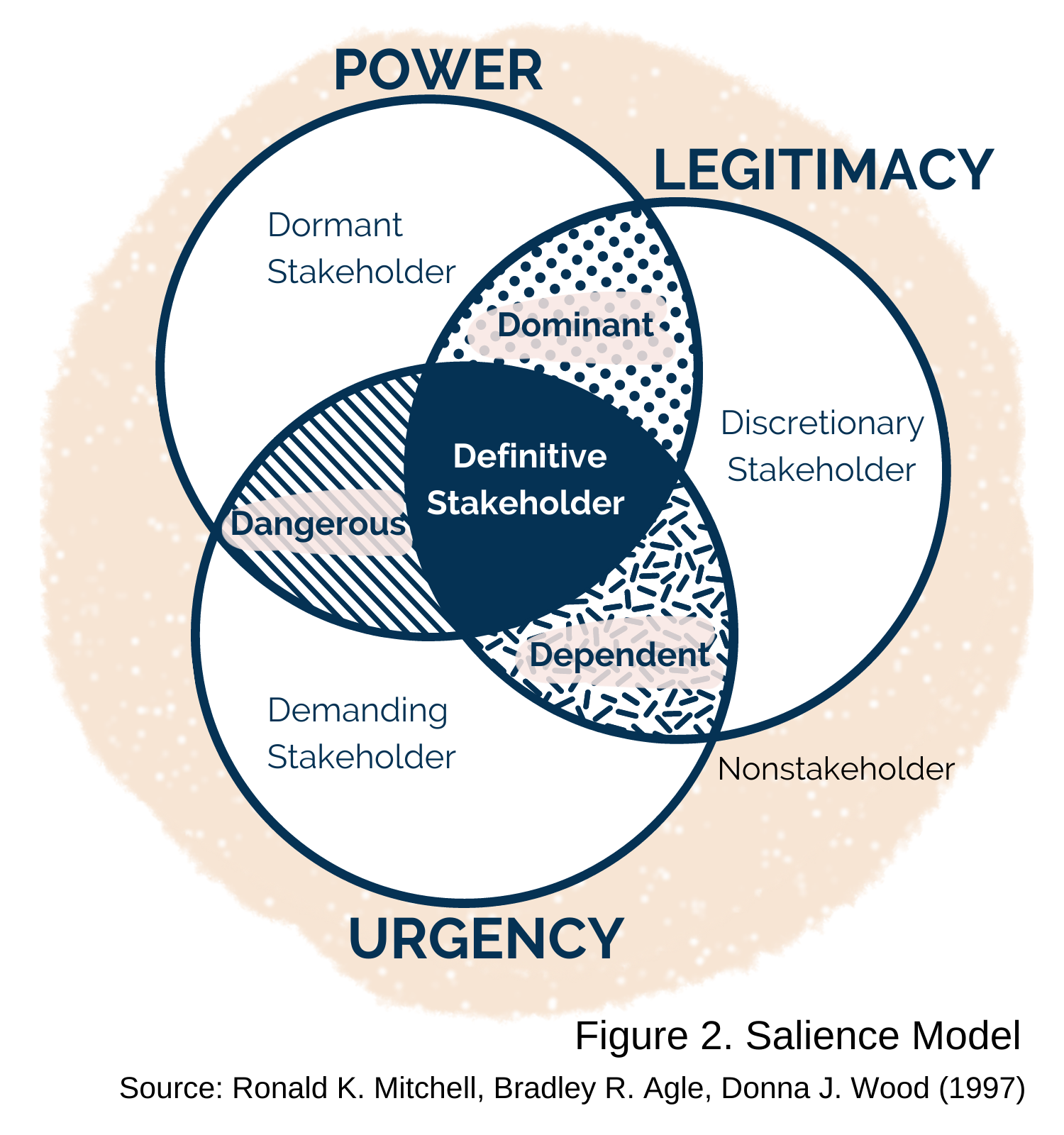

It is not a secret that some HR projects in big corporations have a complex network of relationships and hidden political games in their project scopes. For these projects, it makes sense to use more complex instruments to ensure comprehensive identification and further intentional engagement of stakeholders. One of these instruments is the salience model (Figure 2).

It suggests that “the question of stakeholder salience — the degree to which managers give priority to competing stakeholder claims — goes beyond the question of stakeholder identification, because the dynamics inherent in each relationship involve complex considerations” (Mitchell, R.; Agle B.; Wood, D. 1997). According to this model, stakeholders are classified based on the relative absence or presence of all or some of the three attributes:

- power (level of authority or the ability to bring about the outcomes they desire),

- legitimacy (ones who “really count”),

- urgency (need for immediate attention).

Stakeholders disposed of only one attribute are belonging to the group of latent stakeholders (dormant, discretionary, demanding). This group is worth identifying. However, any special attention and engagement actions to these stakeholders are not likely to be given. The group of expectant stakeholders (dominant, dangerous, dependent) comprises those with two attributes which in most cases lead to an active stance of stakeholders and requires thoughtful analysis and actions from a project team. By acquiring the missing third attribute, any expectant stakeholder can become a definitive stakeholder. This should be carefully tracked, monitored, and reflected in communication and engagement activities by a project team. Thus, the level of engagement between an HR project manager and expectant stakeholders is to be higher compared to latent ones or the same as required for the group of definitive stakeholders.

Stakeholder identification is a dynamic process due to classification attributes being a variable that can change for any particular entity and over time, presenting a constructed reality, and a matter of multiple perceptions.

Stakeholder analysis

Stakeholder analysis is a pillar of stakeholder management and serves as a bridge between stakeholder identification and stakeholder engagement. Often, stakeholders have primary drivers in political, economical, social, technical, and legal fields, which determine their levels of interest in a project. Another important characteristic is the impact or the degree of a stakeholder’s influence on project phases and the final result. These two dimensions provide the basis for the stakeholder analysis and help to rank stakeholders and map them to different groups, for example, actively manage, manage, actively inform and inform. At the next stage, appropriate engagement and communication measures should be elaborated and implemented for each group of stakeholders.

In some projects with matted relationships between stakeholders, there is a need for an additional dimension, for example, level of authority, and/or weighting of applied characteristics to improve the depiction of a stakeholder community. The result of analysis for most HR projects can be presented in a form of a two-dimensional matrix or a three-dimensional cube, aimed at focusing productive efforts of a project team on critical sub-sets of stakeholders. It is worth noting that the characteristics of a stakeholder are not once and constantly fixed values. They do not have a steady state and are often changing over project phases. These changes find a reflection in altering engagement levels of different stakeholders, which can be traced by a so-called stakeholder engagement assessment matrix. The matrix provides a comparison between the current and the desired support levels of a project by stakeholders. Depending on the project’s specifics, any appropriate nominal or ordinal scale might be used to categorize the support levels. The assessment results indicate outliers within the previously identified groups of stakeholders to finetune engagement and communication activities for groups and individuals.

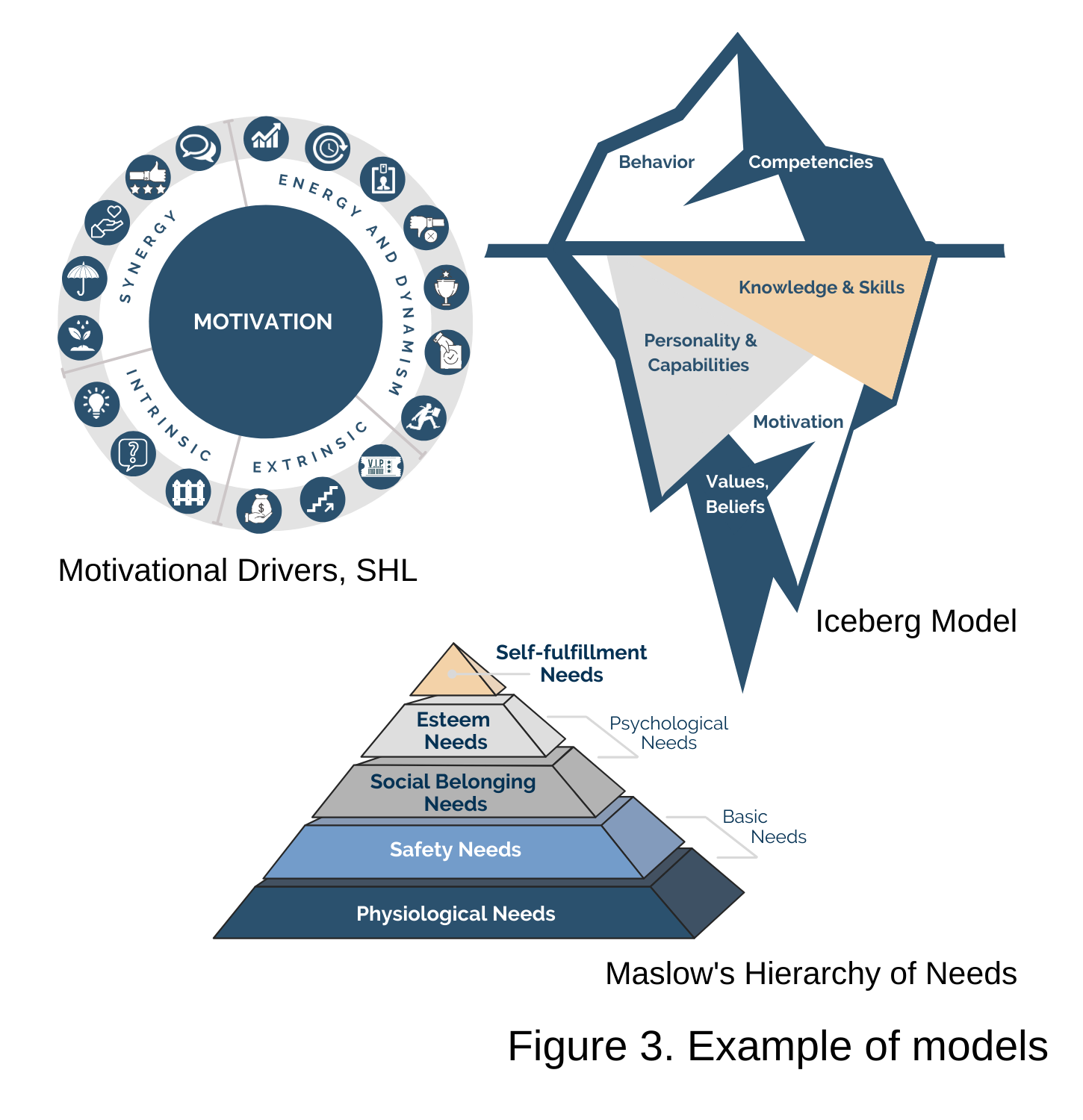

Causes of a stakeholder’s attitude changes can be found in a psychological domain scrutinized by various scientists and practitioners over the last century. The landscape of psychological theories is multifarious and provides a fruitful basis for further development of new models and frameworks and a broad room for its application (Figure 3).

For example, the iceberg model can help to rationalize some unexpected changes in a stakeholder’s behavior. According to this model, the invisible part of human internal drivers is significantly deeper than the visible one. It comprises multiple layers, which in most cases are not purposively demonstrated, but can be triggered at any moment. This is one reason why, a stakeholder might spring up during the project implementation, which can negatively impact the timing, scope, or resources of the project. Another plausible reason is that this stakeholder most probably had that opinion before, but you just did not know it or did not pay enough attention to sustain and develop his commitment.

For example, the iceberg model can help to rationalize some unexpected changes in a stakeholder’s behavior. According to this model, the invisible part of human internal drivers is significantly deeper than the visible one. It comprises multiple layers, which in most cases are not purposively demonstrated, but can be triggered at any moment. This is one reason why, a stakeholder might spring up during the project implementation, which can negatively impact the timing, scope, or resources of the project. Another plausible reason is that this stakeholder most probably had that opinion before, but you just did not know it or did not pay enough attention to sustain and develop his commitment.

Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement is another important component of stakeholder management that ensures the productive involvement of stakeholders in decision making and project execution, according to their needs, interests, and impact. The ultimate engagement goal is to build and maintain the continued commitment of stakeholders during all project phases by instrumentally managing expectations, addressing risks and concerns, clarifying and resolving issues.

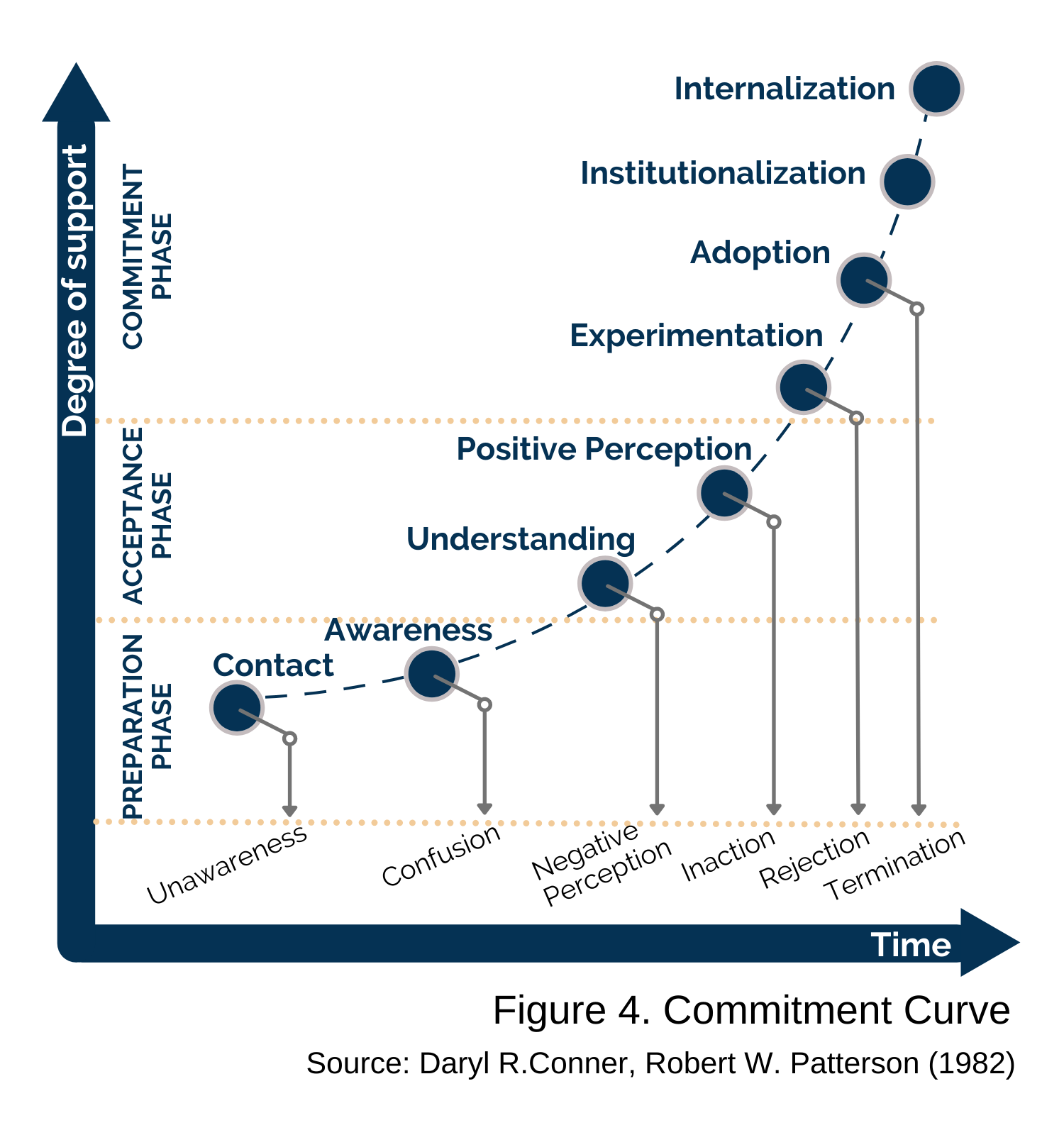

Commitment is the clue that tacks people and the project results. It is an intangible, but noticeable and altering substance, which might be difficult to obtain and easy to lose. The development of stakeholder commitment usually follows the sequential stages of the commitment curve and passes through the main phases: preparation, acceptance, commitment (Figure 4).

This model depicts the critical stages where a stakeholder perception might change from the supportive mode to a blocking one or return to earlier stages, as stakeholders learn more about the project and what it will require from them or give them. Obviously, each stakeholder has an individual commitment curve, which might have a minor or significant deviation from the average pace of the assigned stakeholder group. It explains the appearance of outliers within the classified stakeholder groups.

Altering commitment can be another reason for a stakeholder’s attitude changes and the further necessity to allocate stakeholders to different groups during the project. It also proves the necessity to intentionally monitor and analyze revealed changes, and adapt planned stakeholder engagement and communication activities respectively.

Stakeholder communication

Communication is tightly embedded in the stakeholder engagement process and serves as its engine. It is vitally important for an HR project success to select appropriate methods for delivering the first contact messages to stakeholders, as this is a prerequisite to creating an awareness of the project. There is a wide range of options including a company’s internal media, memos, staff meetings, personal contact, and other mechanisms to launch a forward movement through the stakeholder commitment curve. However, communication efforts do not always produce progress toward the next stages in the way of stakeholder commitment. It is so frustrating when, after many meetings and memos about an initiative, some stakeholders either are not prepared for it or react with total surprise when it affects them. In order to diminish a misunderstanding and possible resistance, proper communication to different stakeholders through relevant channels should be started as early as possible, be transparent, adaptive, clear, and precise.

To ginger up the efficiency of internal and external communications, it is worth thinking over a stakeholder communication plan. Depending on the project complexity and a variety of the identified stakeholder groups, it can be highly detailed or broadly framed. An effective communication plan contains details of what information the project management team will send to, and receive from different stakeholder groups, through what channels information is to be distributed, and how often each stakeholder group is to be approached. As a general rule for HR projects, flexibility and incorporating stakeholder feedback into communications are to prevail over a formal following of the activities that were initially fixed in the communication plan. The stakeholder communication plan is dynamic and a subject of constant changes to address new challenges and issues popping up during a project.

High stakeholders’ commitment and involvement can propel any HR project to the sky, while lack of stakeholder support will tank even a brilliant HR initiative. Stakeholder management is exciting, but a tricky process, which requires continuous attention through all project phases. It is likely to be the first project management area to start with.

References:

-

Freeman, R. Edward, (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman.

-

Freeman, R. Edward, (2004). The Stakeholder Approach Revisited. Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik, 5(3), pp. 228-254.

-

Mitchell, R., Agle B., Wood, D., (1997). Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. The Academy of Management Review, 22(4), pp. 853-886.

-

Conner, Daryl R.; Patterson, Robert W. (1982). Building Commitment to Organizational Change. Training & Development Journal, Vol 36(4), pp. 18-30.

-

Conner Partners, (2018). Building Commitment to Organizational Change. www.connerpartners.com

-

Project Management Institute (2017, 2021). A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide). Sixth and Seventh Editions.

-

Axelos. (2017). Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2®. Sixth Edition.

Read this article on Medium