Problem solving and decision making skills

Every single day, we make dozens of decisions. Some of them are easy-going, and we do not even recognize their processes; others require considerations, and with the rest, one might get stuck in long-lasting thinking. What is decision making, and how does it relate to problem solving? There is a full range of statements from “these processes are the same” to “they are totally different”, or “decision making is a subprocess of problem solving”, and the other way around. I share the opinion that these processes are both active when we need to resolve an issue. They are tightly intertwined, but have different centers of attention.

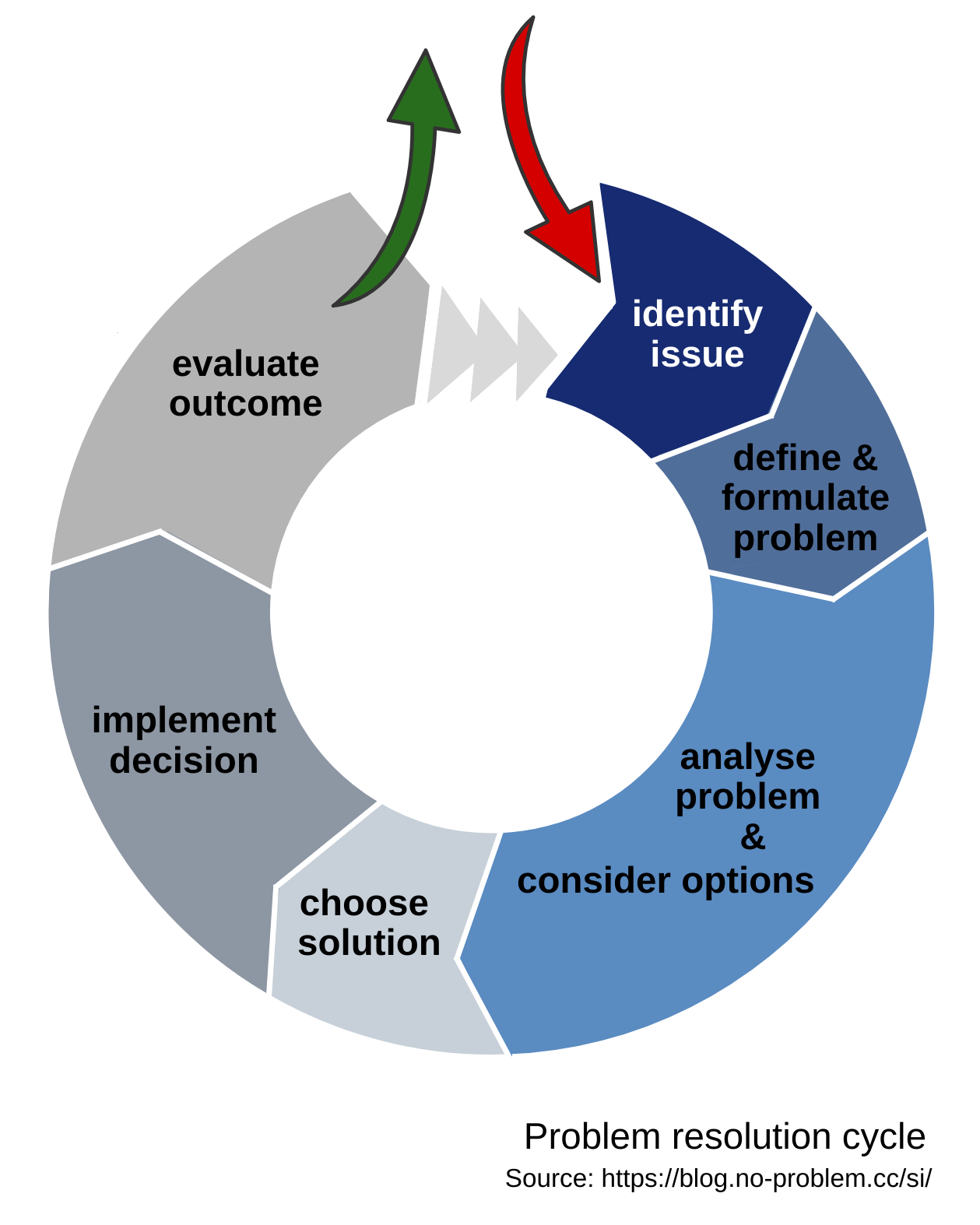

Problem solving is the process of analyzing and understanding a problem, diagnosing its cause, elaborating options, and proposing a solution, which fixes the problem and prevents it from recurring. Usually, ‘decision’ finalizes thinking and comparisons and assumes a commitment to action. So, decision making is the process of identifying and choosing among alternative courses of action in a manner appropriate to the demands of the situation (Kreitner, 2007).

Problems vary in importance, magnitude, or gain and, therefore, require different approaches to decision-making. Decisions are often categorized as routine vs. strategic, generic vs. unique, programmed vs. non-programmed, etc. Their effectiveness and workability may be impaired by a set of different limitations related to the situation’s specific. Every decision is risky. Passive variants, like postponing, avoiding, or not making a decision, are decisions in themselves, which entail consequences and risks. Effective decision making demands precise and accurate strategies that would maximize success, soften restrictions, and mitigate negative outcomes. The common constraints faced by decision makers are the following:

- uncertainty: limited information is available,

- complexity: bounded human capacity to evaluate complicated situations and the consequences of various alternatives,

- time pressure,

- interpersonal issues: a diversity of interests and motivations of involved people requires apt approaches to stakeholder communication and engagement.

Efficient problem solving and decision making are “must-have” skills in the leadership toolbox. Therefore a lot of companies are investing in developing them for their leaders. In order to offer relevant development activities to improve problem solving and/ or decision making in a company, it is necessary to reveal individual gaps of managers in these processes. Some deviations that might be discovered, I would like to illustrate on one of my recent projects, which dealt with the precise assessment of the aforementioned skills. The participants of this assessment and development center had to take on the role of the Business Development Leader of a cable holding controlling three manufacturing sites, which suffer from different sets of problems. In order to sharpen the necessity of taking action, the situation was aggravated by the holding taking on an extremely large and urgent order from a very important customer. After a limited preparation time, participants had to introduce their proposals for handling the situation. Some of the typical gaps that have been demonstrated by participants were:

- George was very fast and decisive. He proposed the most obvious decision (and far from the optimal one): because the technical requirements of the VIP order can only be fulfilled on one site, it has to take it immediately and cancel all current orders by other clients to release the required production capacity.

- Thomas was stuck in analysis paralysis. He calculated the potential development of the cable market and possible shares of holding products for different segments, annual costs of downtime due to equipment failure, and many other things. Unfortunately, when it was the time to present results, he could not formulate any one proposal, but had a list of required additional data to resume his analysis.

- Kate worked carefully through several alternatives, paid attention to their potential benefits and negative effects on the business, but could not select one as her proposal, so she transferred the decision making to the upper level.

- Jan could properly identify and prioritize problems, but narrowed his focus too far, thus limiting his ability to consider alternatives. That led to a decision that was workable, but not the most beneficial for the holding.

- Holly did not consider risks as an important factor and fully relied on her gut feeling.

The list can be continued with each person having his/her own combination of gaps or areas of improvement in the multifaceted processes of problem-solving and decision-making. To work on this, there are plenty of methods and techniques dedicated to fostering these skills. Some of them are general and worth being acquired by everyone; the application of the rest can be most successful and lucrative in specific situations. A turn into active doing is based on a set of different aspects of interpretation of data and information by a decision maker: intuition, experience, perception, judgment, logic, results of analysis, etc., and related to it biases and fallacies.

Read this article on LinkedIn