Effective problem solving

“One should never impose one’s views on a problem; one should rather study it, and in time a solution will reveal itself.” Albert Einstein

Every day there are plenty of situations in which we confront problems, challenges, and routine choices when we want something and do not know immediately what should be accomplished to get it. The desired outcome may be very tangible or abstract. It may be specific or quite general. To obtain relevant results, some physical actions, perceptual and mental activities are required. Simple tasks can be solved without fixating on the methods and necessary steps to reach the result. In complicated situations, there is a need for conscious activities to achieve the desired outcome. A problem-solver has to interact with the situation by appropriately using different cognitive skills and adapting the behavior to the issue specifics. According to Newell and Simon, there are two fundamental problem-solving approaches to apply:

- the recognition method, when a task is decomposed into small known sub-problems;

- the generate and test method, which is based on invention and outside-the-box thinking.

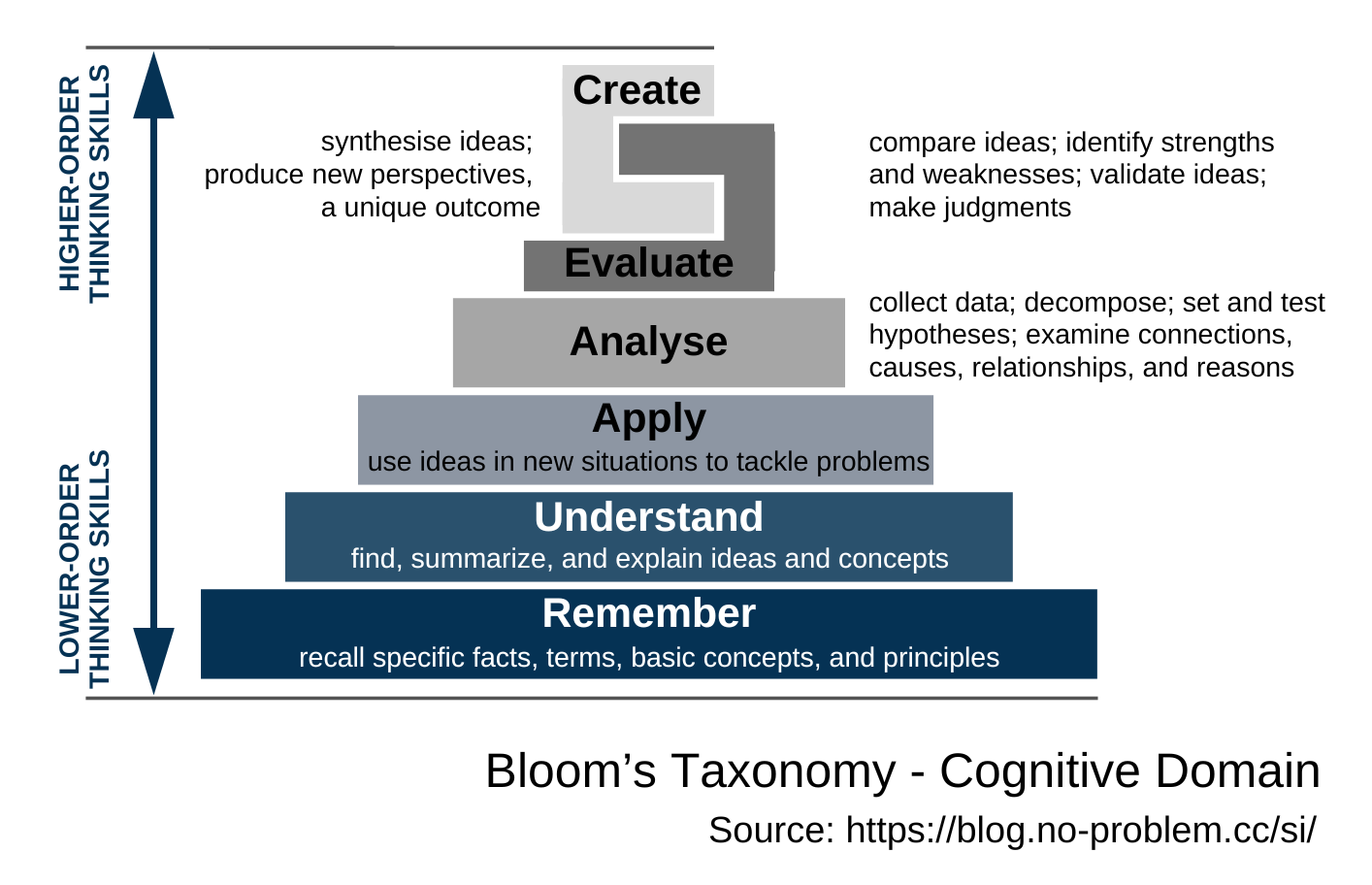

Thinking is the salient point of problem solving and refers to cognitive activities to focus on specific information, process it, discover connections, make decisions, create fresh ideas, validate them, and integrate novel experiences into existing understanding and perception of how things are. These activities are often categorized as lower- and higher-order thinking skills.

Besides this taxonomy, there are a lot of other commonly used types of thinking skills, which can be classified:

Besides this taxonomy, there are a lot of other commonly used types of thinking skills, which can be classified:

- by opposing categories: concrete thinking vs. abstract thinking, convergent thinking vs. divergent thinking, sequential thinking vs. holistic thinking, etc.;

- by approaches: systems thinking, critical thinking, analytical thinking, creative thinking, strategic thinking, design thinking, etc.

I prefer de Bono’s dichotomy of thinking situations by basic types of focus:

- area focus, aimed to reveal new ideas ‘in this particular area’. This is totally free thinking without restrictions to thinking about problems, and goes beyond existing models, methods, and approaches.

- purpose focus, steered to solve the problem. It is grounded to a large extent on experience and concentrated on analysis, judgment, argument, and criticism. This is the more traditional thinking intended to achieve the desired result, to end up with a plan, to make an improvement in a defined direction, and so on.

A combination of diverse cognitive skills, which is varied through different intermediate states, is required to get a suitable outcome in both situation types. A unified, well-paved path from understanding the issue to choosing the optimal solution comprises the following basic steps:

Problem identification

In the business world, most problem-solving situations are purpose-focused and are often ill-defined. The first step in turning spontaneous challenges into well-defined ones is the recognition of the discrepancy between what is the case and what should have been the case. This distinction is called a problem. Not all problems are equal. Some are clearly more important, while others are of greater urgency. The Eisenhower matrix is one of the prominent tools to facilitate prioritization, which helps to divide issues into four categories: do first, schedule for later, delegate, and skip. The difficulty of an issue is another differentiator and can be measured in many ways: whether the goal is achievable, the time required to find a solution, the quality of the solution, and so on. These measures are usually intertwined. In managing complex cases and under time pressure, there is a tendency to accept being ‘less wrong’ now rather than indefinitely pursue an ‘ideal’ solution.

An accurate problem identification allows one to prioritize, determine difficulty, and apply the right level of problem-solving to each situation. When people face an issue, it is necessary to recognize the problem environment — the space in which problem-solving activities take place. It includes information about what is desired, rules, different aspects of the initial situation, the target and its conditions, access to resources, various intermediate states (imagined or experienced), and any known or invented methods, concepts, and procedures to handle it. Clarifying the problem environment and setting a precise problem definition is the next step in making a challenge well-defined.

Problem definition

Problem definition is the essential element of a problem space. It provides sense to an issue and destines its problem-solving. Asking the right questions is a key skill of a problem-solver that aims to unlock the details of a problem environment. Questions that help to think out a problem definition can be:

- When did the problem occur?

- Where did the problem occur?

- What processes/ products/ services did the problem affect?

- How is the problem measured?

- What is the magnitude?

- How much does the problem cost in money, time, customer satisfaction, or another metric?

- …

The more specificly an issue is formulated, the better problem-solving outcome may be expected. To elaborate an accurate problem definition is far from obvious. Sometimes there are needs for decomposition to sub-problems, redefining a problem, or refocusing a purpose, which might result in a change of objectives. Different problem definitions usually lead to different solutions.

Imagine a situation in which John—one of the most experienced developers — leaves a company on a short notice. If the problem is formulated with a very broad focus, like ‘how to prevent damage to a company’s business’, there is a danger to moving right out of the issue into some grand improvement in the business. In such a case, it makes sense to turn from a highly extensive purpose to a smaller and more specific one, like ‘how to replace John in the ongoing projects’; ‘how to retain John’; ‘how to prevent the turnover of other developers’, and so on. Obviously, these definitions do not tackle the same problem, require different problem-solving activities, and differing results should be accounted for.

There are also times to broaden the focus if the original one is too specific. For example, there is a challenge with overcoming stakeholders’ resistance to implementing a new filing system. Using the W5H formula (Who?, What?, Where?, When?, Why?, How?) that helps to extend the problem space, it might be discovered that the problem to solve has nothing to do with this filing system and requires a broader focus with a respective change of target.

To find a promising problem definition, it is necessary to be flexible in considering alternatives, consciously keep trying redefinitions in both directions to the workable level, and see how problem-solving might be carried out. The one to stick to depends on what the desired outcome, available resources, acceptable intermediate states, and other conditions of the problem space are.

Options consideration

If a problem sounds familiar, often the options consideration stage is skipped, and the preference is given to the best-guess approach. If a problem-solver is very familiar with an issue, granularly understands the problem environment, and has a rich knowledge base, (s)he might be able to get good results within the first few guesses. At the same time, extreme familiarity can cause a negative impact because a person might be ingrained with the traditional way of doing things. It may lead to missing minor, but essential differences in the problem space and a failure to make valuable best guesses. Even if the first guess regarding a solution yields a result that falls inside the parameters the problem-solver was looking for, it might be far away from the optimal one. Therefore, it makes sense to include examination of other feasible options in any problem-solving process.

If the problem is defined as ‘how to retain John’, one of the best-guesses could be to make a counteroffer and increase his salary. Assuming that a compensation issue was the only factor that triggered his decision (which in reality is a very rare case), with such a resolution the company may buy John’s loyalty for some period and get a set of risks associated with this option. A closer look at the problem environment may reveal other aspects to take into consideration. For example, pay attention to other factors that motivate or demotivate John, the last changes in his private situation, and so on. This data is a great source to generate a lot of ideas on how to retain him. Some of them hold the potential to be realized under some circumstances, but the rest will be eliminated as pure fantasy.

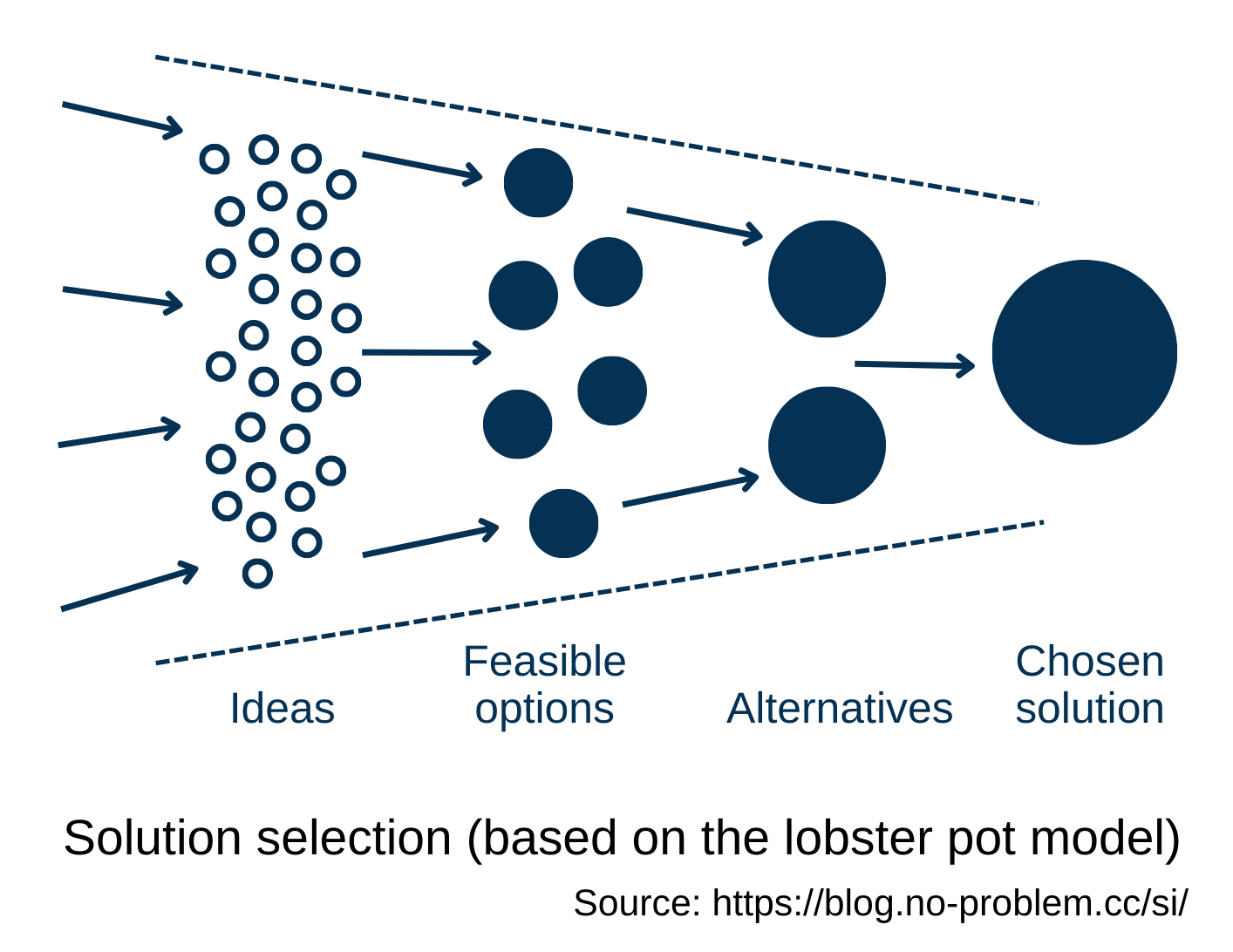

Solution selection

Each solution variant has some prerequisites to be implemented, as well as the accompanying risks that should be taken into account. Comparison of diverse parameters with the defined ones in the problem environment allows a problem-solver to shrink a number of feasible options to several alternatives, which are to be carefully analyzed. Diverse approaches to ranking, weighting, and other methods of analysis can be used to scrutinize and prioritize the selected alternatives.

The result of these activities should be the optimal solution to the defined problem. Sometimes risks associated with the optimal choice might be higher than its potential benefit. Or an expected outcome of its implementation does not meet set requirements. In this case, there is a strong need to return to the problem definition phase and repeat it and the rest of the steps to come up with another solution.

The result of these activities should be the optimal solution to the defined problem. Sometimes risks associated with the optimal choice might be higher than its potential benefit. Or an expected outcome of its implementation does not meet set requirements. In this case, there is a strong need to return to the problem definition phase and repeat it and the rest of the steps to come up with another solution.

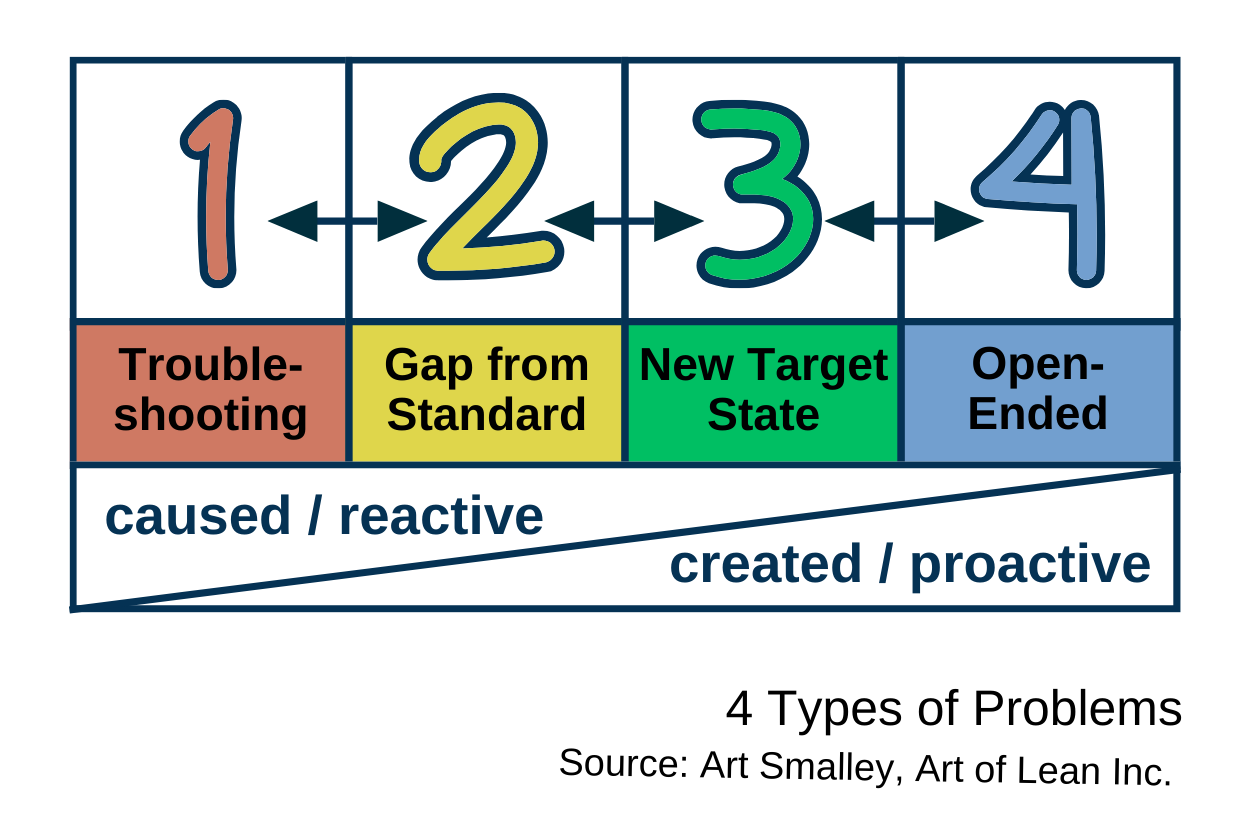

This universal approach is applicable to any simple or complex issue. However, effective problem-solving assumes the fulfillment of each stage tailored to problem specifics. Some issues are the consequence of something going wrong and there is a need to find and fix the cause. Others require proactive preventive actions.

There are four types of problems, which may be classified into two sub-categories:

Caused problem/ Reactive responses

This set of issues appears as the result of a real cause that affected performance and the outcome deviated from the desired one. To grasp a problem under control and respond, some prompt actions are stand in need.

Type 1—Trouble-shooting. These are ‘firefighting’ cases that require immediate actions to reduce damage. If a beamer stops working during a customer presentation, you react to soften the audience’s inconvenience. If a fuse burns out in a test stand, the power must be unplugged. In case an issue requires follow-up activities to trace the cause, the rapid 4Cs problem-solving concept: concern—cause—countermeasure—check results is applied.

Type 2—Gap from standard. These are more severe or repetitive issues that hinder progress and often have a negative impact on the business. If the number of defective items produced on an assembly line is statistically higher than the set limit, there is a need to find and eliminate the root cause. If a noticeable share of projects ends up as a failure or with significant overuse of resources, there is a need to dig deep into processes to make corrections and fix causes. Spotting the root cause is a separate challenge and is usually solved by applying the 5-Why? technique, Ishikawa diagram, Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (FMEA), or other instruments. For Type 2 issues, problem-solving might benefit from the DMAIC approach: define—measure—analyze—improve—control.

Created problems/ Proactive responses

This set is focused on continuous improvement and invention to tackle higher standards and create new opportunities. It generates actions in a constructed future-oriented problem environment.

Type 3—New target state. The main driver of these problems is the pursuit of improvements over existing standards. Compared to the previous two types, the main idea here is not to fix, but rather to push the desired outcome to the next level and proactively create ‘how things should be’ requirements. There are plenty of triggers for a new target condition, like overtaking competitors, extending the customer base, boosting market penetration, advancing processes, and so on. Add-on functionalities in a working product to enhance its productivity and attractiveness for clients and programs aimed at improving customer experience are examples of Type 3 problems. To deal with such an issue, there is a necessity for advanced higher-order thinking skills to create a problem space, draft alternatives, and find an appropriate solution. The Deming cycle (PDCA): plan—do—check—act is the classical model to be based on for approaching continuous improvements.

Type 4—Open-ended innovation. Big innovation problems are entirely created and concentrated on the invention of completely new products, processes, or services. The first iPhone was an example of such a product. Focus on continuous improvement is required, but not enough to solve Type 4 issues. Besides that, creative and design thinking should be actively used that can be supported by the iterative DMADV approach: define — measure — analyze — design — verify.

Solving complex tasks is an iterative and repetitive process, where sometimes the optimal choice can only be seen in retrospect. In dealing with such situations, there is a need for a range of advanced thinking skills and solid methods to recognize issues and handle effective problem-solving processes. Conscious mental activities help to turn any ill-defined issue into a clear-cut one and favor finding relevant instruments focused on an appropriate solution. The above-presented models and techniques can serve as a base to start your journey in a problem-solving universe.

References:

-

Allen Newell, Herbert A. Simon (1972). Human Problem Solving. ISBN: 13-445403-0

-

Edward de Bono (1995). Teach Yourself to Think. ISBN: 978-0-2412-5750-0

-

John Aidar (1997). Decision Making and Problem Solving Strategies. ISBN: 978-0-7494-5551-4

-

Art Smalley (2019). Four types of problems. ISBN: 978-1-9341-0955-7

-

University of Central Florida, Faculty Center. Bloom’s Taxonomy (https://fctl.ucf.edu/teaching-resources/course-design/blooms-taxonomy/)

-

The Peak Performance Center. Types of Thinking (https://thepeakperformancecenter.com)

Read this article on Medium