Decision making frameworks to manage complexity

Drastic political, economic, technological, social, and climate challenges of the last years highlight the chaotic nature of the world and push enterprises to deal with a brittle, anxious, nonlinear, and incomprehensible, so-called BANI-environment. It sparks business responses to explore changes and adjust a company’s objectives to secure its vitality. The ability of organizations to make sense of such triggers is associated with decision-making.

Business decisions are tightly linked to the problem type upon which they are made, and they can be classified as programmed and non-programmed. Programmed decisions are applied in routine or repetitive situations. Usually, some rules and procedures are available to guide such a decision-making process. Cost-benefit analysis and optimization methods are common supplementary components of judgments. Examples of programmed decisions are: pricing, regular equipment service, determining the salary of employees, etc.

Non-programmed decisions refer to messy, ill-structured, or controversial issues and are characterized by a higher level of complexity and uncertainty of the outcome. Decision-making here is an effortful and sometimes difficult process. People tend to apply experience-based patterns to order the context and make sense of things in unknown situations. This is a powerful aspect of human decision-making, but it also brings limitations, like perceptual biases and logical fallacies. To leverage an undertaking, a decision-maker could employ plenty of AI tools for collecting, analyzing, interpreting data, and generating actionable insights. Modern technologies might significantly empower, but not fully substitute, the sense-making process of humans. There are several models aimed at understanding complexity and determining how to decide in a setting with a wide range of undefined challenges.

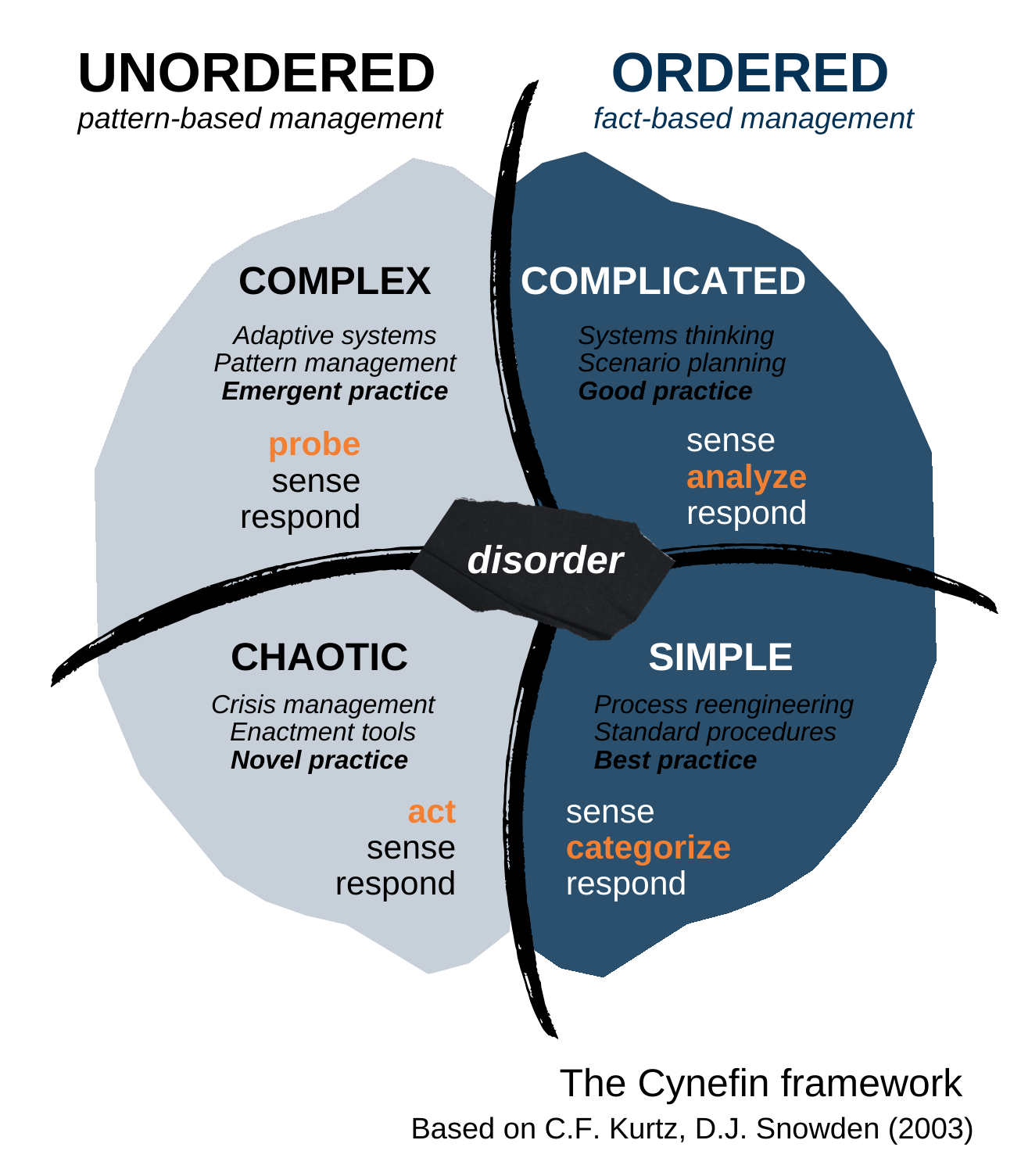

The Cynefin framework

One of the effective instruments that can be used in dealing with intractable issues is the Cynefin framework, created by Dave Snowden. “Cynefin” is a Welsh word meaning “habitat”. The model has two sizeable areas: ordered contexts, where cause-and-effect relationships are tangible; and unordered contexts without an immediately apparent relationship between cause and effect. They embody four open domains and a fifth central space. It is a powerful decision-making aid, especially in the management and consulting fields, which helps structure sense-making to understand and position a problem within the context realms and offers strategies to handle it.

- Simple contexts: the domain of best practice. This is the space of “known knowns”, and stakeholders share a common understanding of an issue. To ensure consistency, structured techniques are embedded into processes. When the facts of the situation are assessed and properly categorized, the right response is self-evident and undisputed. Potential pitfalls associated with this domain are: incorrect classification because of oversimplification of issues, blindness of decision makers to new ways of thinking, and sliding into the chaotic domain because of missing or untimely recognition of essential changes of the context.

- Complicated contexts: the domain of experts. Complicated situations often contain multiple possible right answers. It is the area of “known unknowns” that requires systems thinking, in-depth analysis of the relationship between cause(s) and effect, and expertise to tackle a problem and to find a suitable response. It calls for an investigation of alternatives and an understanding of consequences, which not everyone can handle. The feasible obstacles for this domain are: “analysis paralysis”, which is being unable to agree on any solution, and entrained thinking patterns that might block creativity or lead to a false conclusion because of an initial assumption error.

- Complex contexts: the domain of emergence. This realm is “unknown unknowns” relationships without apparent cause and effect, and with no obvious right answers. The BANI-environment pushes much of contemporary business in this direction. The decision model deploys experimentation to create and pilot some regularities before any action is rolled out across the organization. However, in complex environments with unpredictable changes, there is no guarantee that what worked once will be effective the next time. Thus might stimulate the temptation of decision-makers to fall back into traditional command-and-control styles with low tolerance to failure, impatience with delays of desired achievements, and micromanagement, which impede the opportunity for informative patterns to emerge.

- Chaotic contexts: the domain of rapid response. This is the turbulence space without existing manageable patterns and with swinging relationships between cause and effect, so that they are extremely difficult to determine. This is the domain of unknowables, with the demand for immediate, decisive action(s). Decision makers do not have enough time to investigate change. Concurrently, people might be more open to novelty, innovation, and out-of-the-box thinking. The decision strategy in this realm is to act quickly to stabilize the situation, then to sense the rapid reaction to the made intervention, and to respond by transforming the state from chaos to complexity.

- Disorder is the area of collision when decision-makers look at the same situation from different points of view. The way out of this realm may require breaking down the case into smaller parts and assigning each of them to a fitting one of the other four domains.

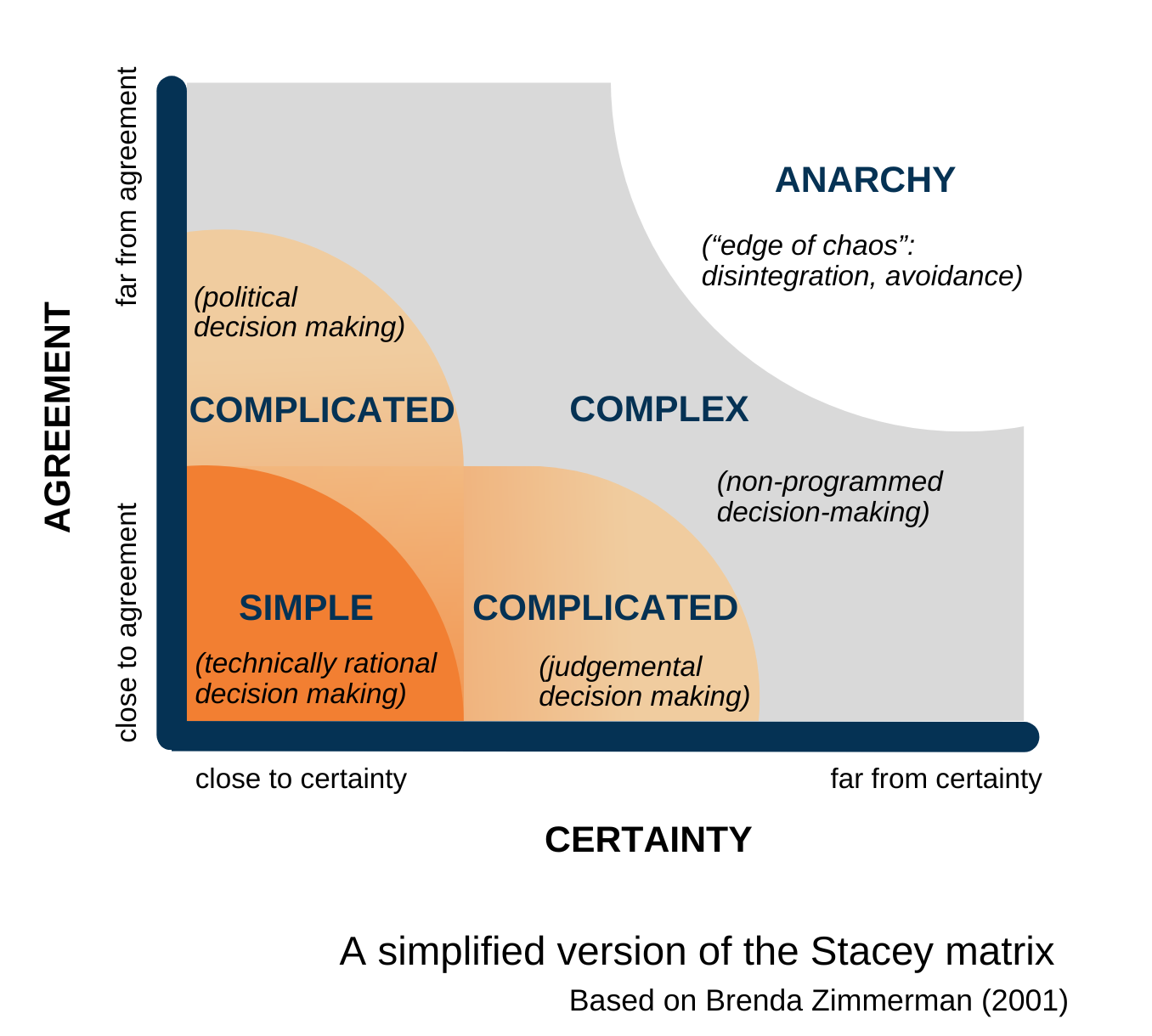

The Stacey matrix

Another technique that helps discriminate between various forms of complexity and choose suitable actions to address the issue is the Stacey matrix. It is commonly used in diverse business contexts, and its application is extremely relevant in the project management field. The model was developed in the mid-1990s by Ralph Douglas Stacey to guide management decisions in a complex adaptive system and has two dimensions: the degree of certainty and the level of agreement over events. Decisions that can be extrapolated from the experience to predict outcomes of an action, or when cause-and-effect relationships are distinctly determined, are located in the “close to certainty” zone. At the other end of the certainty continuum are “far from certainty” decisions. They are associated with unique, or at least new to decision-makers, situations and often have no clear cause-and-effect linkages. Members of a group, team, or organization might have differing views on the event, an appropriate decision, or how to tackle a case. The matrix reflects these concerns, and the vertical axis measures the level of agreement about an issue or decision among stakeholders. As a result, the events’ landscape falls into categories:

- A simple zone is the realm of sound management practice for issues and decisions. On the matrix, it is close to certainty and close to agreement. To address a problem here, a decision-maker has to handle techniques that allow gathering data from the past to use them to predict the future, to design actions, control and monitor results against the detailed plans.

- A complicated area can be split into political and judgmental decision-making zones. Some business cases have high certainty about how outcomes can be created, but a low level of agreement about which objectives are desirable or most valuable. So, decision-making tends to be political rather than a technical action and requires skills of coalition building, negotiation, and reaching a compromise to create a business agenda that is acceptable to multiple stakeholders. Other complicated situations are when issues have a high level of agreement about desired outcomes, but moderate certainty about the cause-and-effect relationships to create these results. This is a judgmental domain. The goal of decision-making here is to create a strong sense of a shared vision among interested parties and apply a flexible approach to planning, while comparisons will be made against the mission and vision for the organization instead of detailed and fixed plans.

- A complexity zone covers a large realm where the combination of minor levels of both dimensions: agreement and certainty, transforms an issue or a project into a complex management problem and might trigger poor decision-making practices, because traditional “learning from the past” approaches are not very useful. This is a field of innovation and non-programmed decisions, where systems thinking, adaptivity, and agility are key skills for effective decision-making and creating new operating models.

- Area of anarchy. Situations with tremendous levels of uncertainty and disagreement often lead to chaos and should be avoided by organizations as much as possible. The traditional methods of planning, visioning, and negotiation are insufficient in these contexts; therefore, a highly open-minded approach of decision makers to tailor strategies is needed to address breakdown cases should they occur.

An application of the Stacey matrix finds recognition in different business areas, while it allows hitting the following targets:

- choosing between management approaches for a specific issue,

- making sense of an array of decisions,

- communicating to others why a particular approach is appropriate,

- nudging the system to the edge of chaos by deliberately increasing the uncertainty and disagreement to foster innovations.

Most business decisions are related to ambiguity, and a decision-maker is forced to take some risks. There are plenty of instruments and decision-making models aimed at supporting the process. However, effective decision-making is a critical responsibility for managers and requires a variety of knowledge and skills to guide the undertaking, to select and tune approaches depending on the situation’s type, to eliminate risk, and to adapt leadership styles to best suit the case.

Read this article on LinkedIn