An inability to reach an agreement:

is it always a conflict?

Conflicts are part of any organization. Some of them have a destructive nature that ruins a productive working climate. Others are essential elements to synchronize different points of view during problem-solving that drive a team towards common targets. Usually several parties are involved in a conflict and it has a real cause or a set of causes that lie in various clusters: scarce resources, cost, priorities, processes, personal work styles, lack of competencies, missing or inappropriate ground rules, personality issues, etc. Ignoring or postponing conflict resolution with a real cause might lead to frustration, anger, and blooming faultfinding behavior.

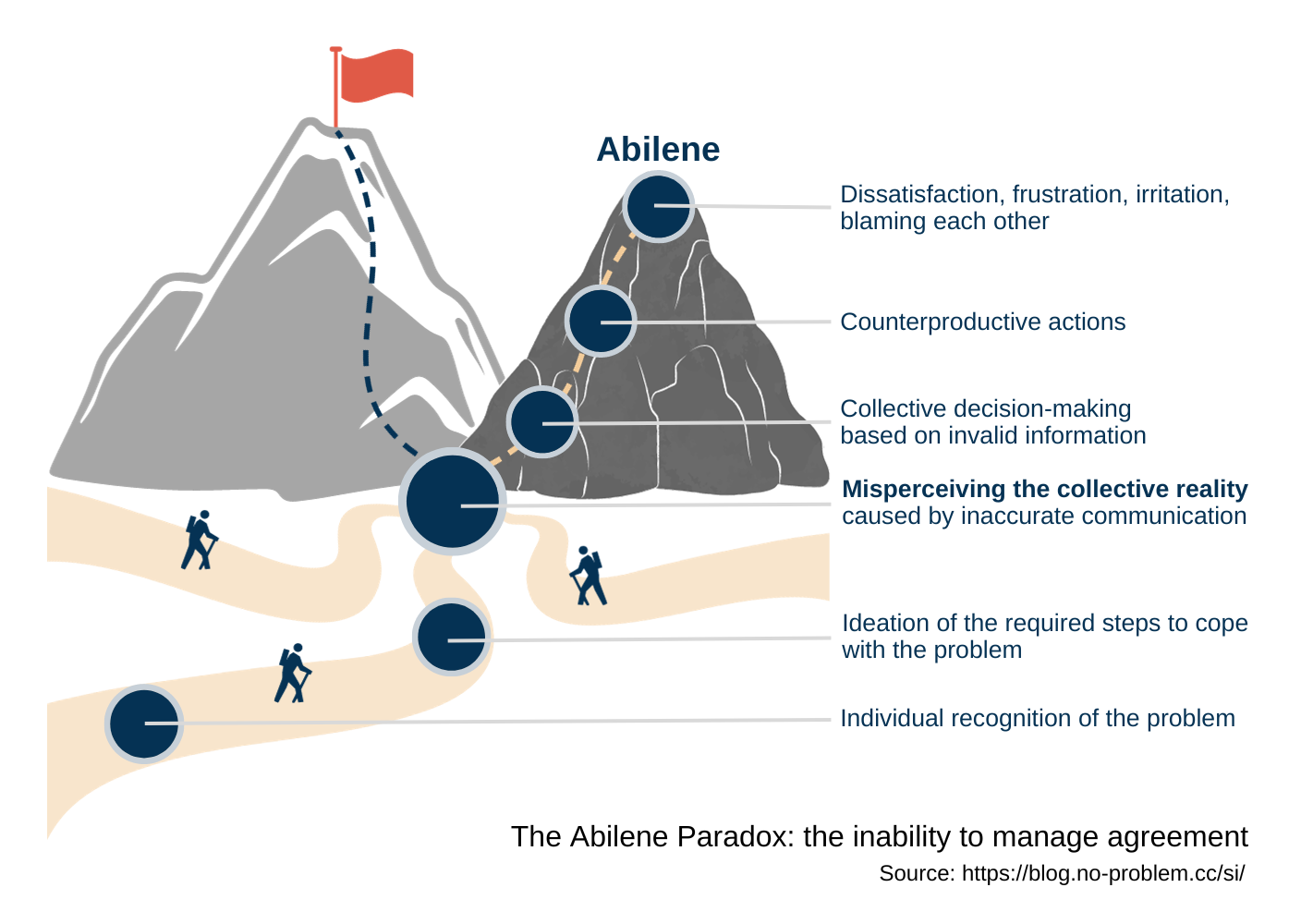

Blaming behavior is a solid unhealthy symptom of a company and, often by default, it is assigned to the inability to manage conflict. However, it might result from the so-called Abilene paradox, when there is no real conflict cause and involved people concur on the actions they want to take and then together do the opposite. Jerry B. Harvey says: “Organizations frequently take actions in contradiction to what they really want to do and therefore defeat the very purposes they are trying to achieve.” It sounds absurd to some extent, but it happens more often than one could think.

Several years ago, I was a business partner of one industrial division that operated in a highly competitive market and had very demanding big clients. One day, a country account manager brought great news — the biggest local client wanted to replace its current automation system with the most modern and advanced one. The required technology was already piloting in the company in another country but on the local market, neither this division nor their competitors had ever undertaken such a project before. At the same time, this 7-figures project was considered a profitable one, and it also was seen as a door opener for a new market niche in the country. The division’s headquarters has agreed to support the local team. The country CEO was excited and pushy about this project because its implementation could advance the businesses of other divisions with this customer. The country division lead has already visualized how this project would strategically change the opportunity block for his business. The head of engineering looked forward to the acceleration of building up-to-date technical competencies and massive knowledge transfer to his department. The commercial division lead was satisfied with the planned project margin and checked that major risks had been considered. The project lead was motivated to take on this career-boosting challenge and actively participated in preparation for the tender. After a tough fight with competitors during the tender, the division won the project. The project plan was updated, monitoring systems were set, and the exciting journey began. After one year of execution, the project status became red. At the end of the second year, the company was fighting to reduce penalties.

During the lessons learned session, it was discovered that key decision-makers who could influence the ‘no-go’ decision and stop this project did not share and properly articulate their concerns with others. The head of engineering discovered that the headquarters’ technical department had used a lot of contractors and subcontractors for the pilot and, in fact, had limited relevant in-house knowledge. So, knowledge acquisition became more complicated. He reported it as one of the risks but did not set the red flag for the project to start, because he saw how excited the rest were about the project. The division lead had a bad feeling about the project because the client was known as fault-finding and often changing an agreed work scope. However, he did not want his weird experience to damage opportunities, and believed in the professional mastery of the project manager and head of engineering, who seemed not to have strong doubts about the project’s success. Besides that, he could not report to the country CEO or HQ management gut feelings instead of confirmed facts. The commercial division lead was surprised that some risks were evaluated lower than she would expect, but as they were all from the technical side, she relied on estimates and mitigation actions suggested by the responsible colleagues. The project manager knew that the project would be complicated from technical and organizational points of view, with a real chance of failing because of diverse factors. He also saw an enormous inspiration about the project and support from all sides. So, he decided to do his best to be a good team player and focused on avoiding mistakes in project management processes.

In the described situation, there was no real conflict cause, directly the opposite: all decision-makers wanted to support each other and to achieve the same target. On the individual level, each of them recognized a problem and knew how to cope with it. However, their inaccurate communication led to a misperception of the collective reality. This point was the fork in the road where the team went off the desired path and headed to Abilene. Then, with invalid information, members took collective decisions that started actions contrary to what they wanted to do, and arrived at the opposite results: instead of new lucrative business opportunities there were losses of money and to some extent competitive advantages and reputation. The paradoxical nature of this issue is the inability to manage agreement: on the surface, it looks like team members have aligned their interests and agreed on actions to achieve a common target. But inside, their decision-making was based on misrepresented data and actually the team was far away from an agreement that its members indeed wanted to have.

For a small or mid-sized company, such an Abilene trip can turn out to be the final destination of its business. For a big company with a stronger margin of business safety and bigger resources the situation might develop further and according to Harvey affects working productivity and well-being: “As a result of taking actions that are counterproductive, organization members experience frustration, anger, irritation, and dissatisfaction with their organization. Frequently, they also blame authority figures and one another.” If the paradox is not recognized and appropriate corrective actions are not taken, most probably it ends in Abilene and then will repeat itself with greater intensity.

For a small or mid-sized company, such an Abilene trip can turn out to be the final destination of its business. For a big company with a stronger margin of business safety and bigger resources the situation might develop further and according to Harvey affects working productivity and well-being: “As a result of taking actions that are counterproductive, organization members experience frustration, anger, irritation, and dissatisfaction with their organization. Frequently, they also blame authority figures and one another.” If the paradox is not recognized and appropriate corrective actions are not taken, most probably it ends in Abilene and then will repeat itself with greater intensity.

There are plenty of reasons why team members are not able to manage an agreement. One of them is the fear of being tabbed as a “non-team player”. The dominant trend in organizational development focusing strongly on teamwork and positive thinking besides the obviously positive side that ensures the development of breakthrough technologies and businesses might serve as a greenhouse of an individual’s fear of being one who spoils a team’s common inspiration and excitement. Another reason is deeply rooted in the dimension of corporate culture, when disagreement could be considered as ‘disloyalty’ and no one wants to be a messenger that brings bad news. The list of grounds can be extended to various aspects of psychology, human perceptions, individual values, motivation, and group dynamics.

The paradox can be revealed on the way or post factum. Anyway, a search for the culprits is not the right action to take. It is counterproductive and diverts a team from problem-solving required to redirect a company along the route it really wants to take. Attempts to eliminate the paradox by applying standard methods of conflict resolution are doomed to fail, because any Abilene trip is the inability to manage agreement, not the inability to manage a conflict. The power to destroy the paradox comes from speaking to the underlying reality of the situation. Therefore, accurate messaging and a corporate culture that favors fearless and open communication are the keys to being able to manage agreements really beneficial for a company.

Read this article on LinkedIn